Introduction: Asking the Big Questions

Konnichiwa. Welcome to the AI Automation Dojo, where we look at the corporate world’s obsession with doing things the biggest, most expensive way possible and ask, are you guys okay?. Today we’re putting down our process maps and picking up a controller to talk about a video game. I know, I know, but trust me, we’re diving into the shocking, brilliant story of Claire Obscure Expedition 33.

I’m your host, Andrzej Kinastowski, one of the founders of Office Samurai, where we believe that a cohesive vision is worth more than a billion dollar budget. So, whether you’re a team lead trying to inspire greatness, a CEO wondering why throwing more money at a problem isn’t fixing it, or just a fan of a damn good story, you’re in the right place. Now, grab your favorite katana, or in this case a classified sword of unbelievable financial efficiency, and let’s get to it.

Discovering the unicorn game

I only have the time to play about two video games a year, and earlier this year I decided it was time for one. I fired up the store, ready for the digital parade of usual suspects. I scrolled past generic Space Marine Shooter 6 and the definitive HD remix of a game I barely remember playing on a console that now doubles as a doorstep.

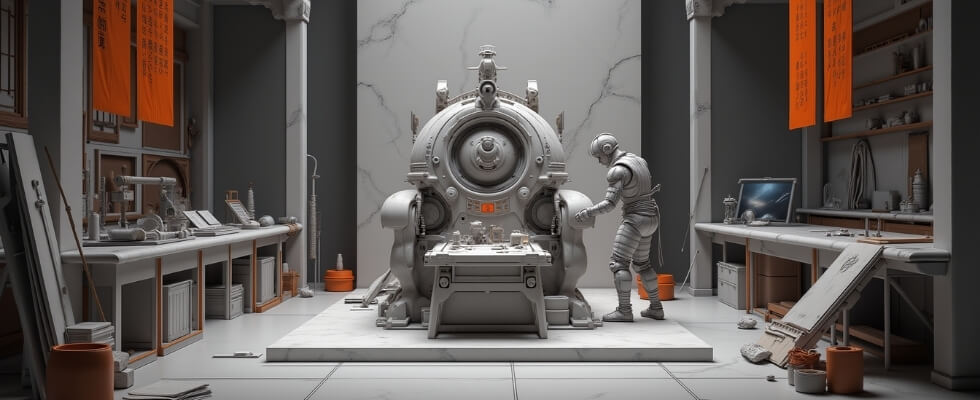

And then I found something that looked different: a game called Claire Obscure Expedition 33. And let me tell you, after I started playing, I had a full-blown Keanu Reeves moment. I got through the prologue and I just went: “whoa”. I finished the first act and I went: “whoa”. 40 hours later, as the credit rolls on the ending, it was a profound “whoa” because I genuinely, desperately did not want it to end. I loved this game. Everything just worked. The graphics weren’t just pretty, they were a moving painting with a style so distinct, every frame was a painting. The music wasn’t just a background track. It was the story’s heartbeat swelling and receding with perfect emotional timing. And the characters, these weren’t cardboard cutouts spouting generic fantasy dialogue about taking an arrow in the knee. They were fully fleshed, believable, flawed people brought to life with a level of motion capture and voice acting I don’t think I have seen before.

The AAA industry standard: brute force model

It’s been a long, long time since a piece of media, any media, has impressed me this much. You go into the digital petting zoo, expecting to see the same tired goats and a deeply unenthusiastic llama, but instead you find a unicorn. Most of the games you hear about are what we call AAA titles. The typical AAA game has a core team of anywhere from 250 to 500 people. The core doesn’t count contractors, voice actors, orchestra, or the person who orders the pizza. For the biggest titles, like Red Dead Redemption 2 or GTA V, we’re talking a thousand people or more. The budget? A cool 150 to 500 million dollars. Yes, you heard that right.

We’re talking about a group of people the size of a small town and a budget that could probably fund a mission to Mars, all to create something that half the time is buggy on launch. It’s a business model built on brute force. It’s a recipe for blandness because when you spend that much money, you can’t afford to take risks. You end up with the interactive equivalent of a beige Toyota Camry. A game is considered a success if it sells between one and five million copies. Anything less than a million is a certified disaster. Even with all that money and manpower, these games often get mixed reviews. A 7 out of 10 on Metacritic is pretty standard, which basically translates to “it was okay”.

The industry-shaking phenomenon

Now, back to our hero, Expedition 33. The game was getting rave reviews from every major outlet. Then I went to Metacritic, and this is where the story goes from great game to industry-shaking phenomenon. As of this recording, the user score for Claire Obscure Expedition 33 is 9.7 out of 10. That’s not just high. It’s a statistical anomaly. The next closest is a 9.3. That gap isn’t a small step. It’s a chasm.

The game has already sold 5 million copies as of October 2025. But here’s the real kicker, the part that should be giving executives night sweats: the team and the budget. This masterpiece was created by a core team of just over 30 people. The budget, while not officially disclosed, is estimated to be no more than $30 million.

Let that sink in. They used, let’s be generous, one-tenth of the people and one-tenth of the budget to produce a game by popular consensus infinitely better than games made with ten times the resources. That’s not just an upset. It’s a fundamental change to the entire industry’s logic. It shouldn’t be possible.

So the question is, how? How does a small studio from France named Sandfall Interactive deliver something that outclasses the biggest names in the business?. I started digging. I read reviews, watched interviews, and listened to the creators. And I started to see patterns, a set of rules that allowed them to create something so extraordinary.

This isn’t just a story about a video game. It’s a story about David versus Goliath, about passion versus profit. I’ve distilled their success into three rules.

Rule 1: Make the game you want to play

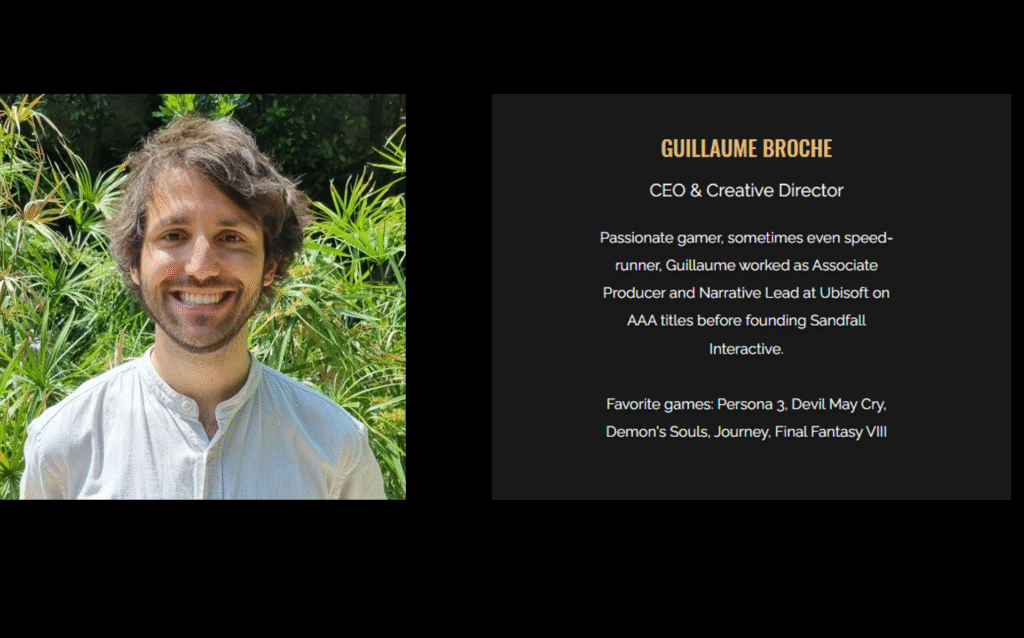

The first rule revolves around Guillaume Broch, the visionary, the driving force behind Expedition 33. His story starts at the place you might know, Ubisoft. Guillaume was a cog in that machine, working on games that, by his own admission, he wasn’t even excited to play. He realized he was helping to paint the bars of his own prison. He was bored.

He had an idea for a turn-based Japanese-style RPG. Walking into a major publisher like Ubisoft and pitching a new, unproven turn-based JRPG is like walking into a shark tank with a steak strapped to your head. Big studios are allergic to risk. So Guillaume looked at the corporate mantra to accept things as they are, and his response was essentially, “nah, I’m good”. And he left.

He started by learning Unreal Engine 5. He roped in a few friends, and together they cobbled a demo. Against all odds, they secured funding. He always says the same thing. He just wanted to create a game that he himself would have loved to play.

That, right there, is the first rule: Make the game you want to play. In other words, build something you know inside and out. Create from a place of passion and deep, personal understanding. It’s about empathy. It’s about knowing your end users so well that you can anticipate their needs before they even know what they are.

Rule 2: Talent and will over skill

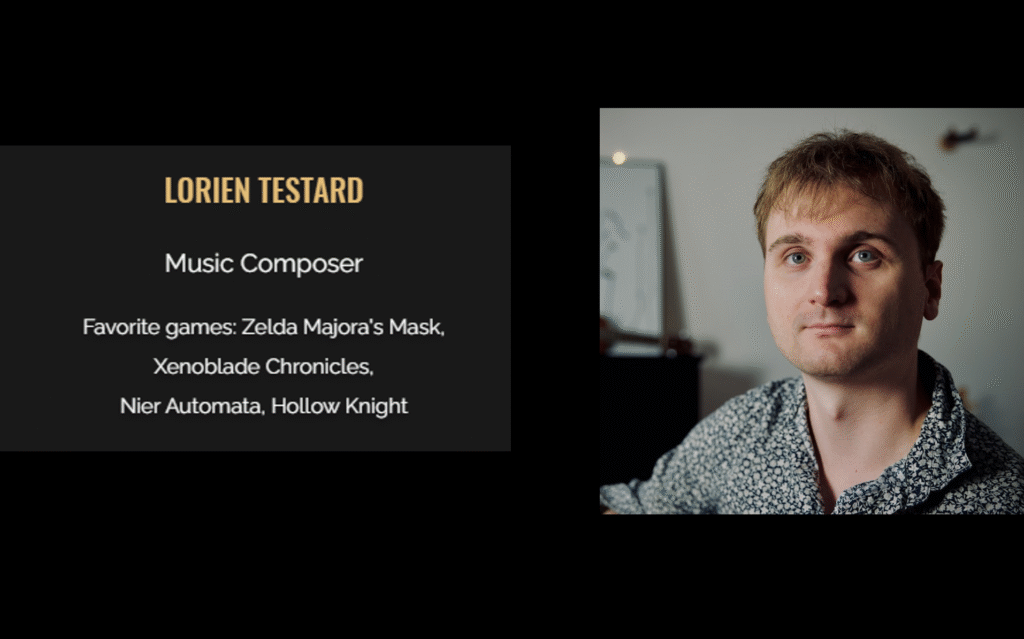

That doesn’t explain how a tiny team on a shoestring budget created a technical and artistic marvel. This brings me to the second thing: the soundtrack. The soundtrack for Expedition 33 is a sprawling, epic masterpiece. We’re talking 154 tracks over eight hours of music.

The game music toppled the actual real life music charts in several countries. And it was all created by Lorien Testard. This is the first soundtrack he has ever composed. Before this, he was a classically trained musician and a guitar teacher. He posted his best work on some obscure French forum for indie game developers.

Guillaume Broch was browsing that same forum looking for a composer. He heard Lorien’s work, loved it, and reached out. I can only imagine the conversation: Guillaume slides into his DMs: “Hey, love your stuff, wanna score our career-defining epic RPG?”. And Lorien types back: “Absolutely, full disclosure though, I’ve never actually scored a video game before, is that a problem?”. And Guillaume just replies: “Buddy, we’ve never made a video game before, you’ll fit right in”.

This first timer thing, it turns out, is a bit of a theme at Sandfall Interactive. The lead writer had never written for a game. In one interview, someone asked Guillaume if it was true that over 50% of the team were juniors with little experience. And Guillaume just laughed and said, “oh, it was probably closer to 80%”.

How does a team composed mostly of people who on paper have no business even making a game go on to create one of the most successful games of the decade?. And this brings us to rule number two: talent and will over skill.

When Sandfall Interactive was hiring, they were obsessive. They weren’t looking for the most impressive resume, they were looking for a specific kind of person. In his own words, Guillaume was looking for the real spark in their eyes. Why? Because he understood a fundamental truth: You can teach skills, but you cannot teach passion. You hire for the spark because the spark is what gets you through the five years of brutal, painstaking development.

It is far better in the long run to hire raw, passionate talent and shape them than to hire a skilled mercenary who’s already jaded. Their inexperience was in many ways their greatest asset. It allowed them to approach problems with a fresh perspective to create something new because they didn’t know the rules they were supposedly breaking.

Rule 3: Hire talent and let them work

The final rule is the one that every manager with control issues needs to have tattooed on the inside of their eyelids. With Expedition 33, it shows with the silent partner in their creative endeavor, the publisher. In the AAA gaming world, the publisher is often less of a partner and more of a backseat driver.

But the publisher for Claire Obscure Expedition 33 was a company called Kepler Interactive. They’re like the anti-publisher. They’re a publisher and a game developer built on a co-ownership model. This means that people in charge of the money understand that creative vision can’t be micromanaged into existence.

So what did they do with Sandfall Interactive? They gave them the money and then, and this is the crucial part, they left them alone. Guillaume himself said Kepler supported them all the way while giving them total creative freedom. They believed in the vision enough to not screw with it.

And this is the final and perhaps most important lesson here: Hire talent and then for the love of all that is holy, let them work. If you’ve actually hired a team of talented, passionate people, then guess what? They are better at their jobs than you are. Your job isn’t to steer the ship. It’s to build a great ship, hire a great captain, and then get off the bridge. Trust your team.

Conclusion and blueprint for success

So there you have it. The three rules that I believe allowed a tiny French studio to build a masterpiece that put the titans of the industry to shame:

- Make the game you want to play. Create from a place of deep personal passion and empathy.

- Talent and will over skill. Bet on the fire in people’s bellies, not just the certificates on their walls.

- Hire talent and let them work. Trust your people and give them the freedom to be brilliant.

This is a blueprint for creating anything amazing. It’s proof that a clear vision, a small dedicated team, and a whole lot of trust can achieve something that a thousand people and half a billion dollars can’t. They can create something that makes people stop, look, and in the immortal words of Keanu Reeves, just say, “whoa”.

And that’s the final quest marker for this episode. We’ve reached the end credits of the incredible story of Expedition 33. Dōmo arigatō for lending us your ears. A massive thank you as always to the core team behind the operation, and our producer, Anna Cubal, who ensures our final product is a masterpiece and not a buggy release before it’s ready. We record this at Wodzu Beats Studio, our own small indie studio.

Follow us on social media for more insights that are hopefully more successful than a typical AAA game launch. Now, the game leaves us with a critical question: What will you paint?. Until next time, remember to question the way things are done. Mata ne.